What I Did Over My Summer Vacation

July 6, 2015

Day One

That’s the Eyrie Vineyard in the Red Hills of Dundee, Oregon. David Lett first planted here in 1965. The red-tailed hawks the winery was named after still nest in the tall evergreen at the top of the slope.

Eyrie’s Original Vines (still bottled under that name) include the first pinot noir in Oregon. The Original Vines section is above the break halfway up the hill, where the orientation of the rows changes from going up and down the hill to side-by-side. The plot on the left shaped like the lid of a grand piano used to be a section of the Eason Vineyard. Eyrie bought it in 2011 (you can see why!) and now bottles the old Eason vines as the Eyrie Outcrop Vineyard.

At 50 years old, the Original Vines are gnarly and as thick as a man’s neck.

Like many of the original plantings in Oregon, they are on their own roots, vitis vinifera all the way down. There is some phylloxera in the vineyard—the affected vines don’t produce as much foliage (or grapes).

Jason Lett found a dead soldier and brought it back to display in the tasting room.

The spots of soil peeking through the grass and wildflowers are red Jory clays dating to a volcanic eruption that covered the area 50 million years ago. The whole Dundee Hills area has darker or lighter variations of this.

Different clones are peppered throughout the vineyard more or less randomly. Above, Jason compares the leaves from two chardonnay plants. They’ll each ripen at their own pace and get harvested together. “It’s funny when someone picks everything at uniform ripeness and then throws it in 37 different kinds of oak to add complexity,” Jason remarked.

We got here in the middle of a heat wave—several days of 100-degree temperatures at high noon. Workers were clearing leaves from the bottom rows of the trellises where the grapes grow to help with ventilation. Most of the vineyards around here also have the vines trained higher up from the ground than in Burgundy for the same reason (and to keep them further away from the heat-retaining earth).

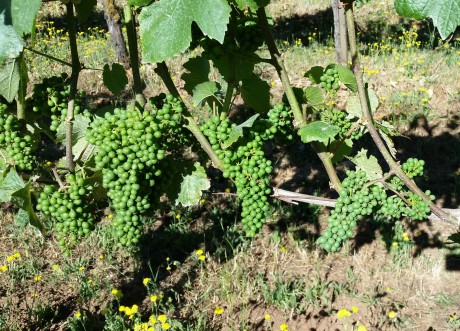

It’s going to be an early harvest this year. Jason Lett made the call not to prune the wings and shoulders—protrusions off the side like the one in the bunch on the right, which will ripen behind the rest of the cluster and act as a natural acidifier. He’d rather get the acid this way than by buying sackfuls of tartaric acid to pour into the vats in the winery, since there are many kinds of acidity in grapes but just one in the sacks.

Some of the barrels at the winery are thirty years old. There are other neutral vessels, too.

These wines don’t taste like other New World pinot noirs.

The Eyrie Vineyards 2012 Original Vines Pinot Noir is so profound I’m posting this even though the picture is out of focus. Don’t miss it! The new labels were painted by Jason Lett.

I am not normally one to photograph food, but if you are ever in McMinnville, Oregon, you need to get lunch at the Valley Commissary.

McMinnville’s main drag also hosts several tasting rooms I was not tempted to visit.

DAY TWO

Here are the gates to Cameron’s Clos Electrique vineyard (named after its electric fence). Looks kind of like Clos Vougeot, but much smaller.

The winery is above the vineyard near the top of the slope, like Clos Vougeot.

The vines here are also on their own roots—I spotted a bit of provignage going on.

There’s that red Jory soil again.

Most of the barrels in the winery are old, up to about ten years. New oak is only used for the entry-level wines. Assistant winemaker Tom Sivilli gave us the chance to taste some Clos Electrique and Abbey Ridge samples side by side—Abbey Ridge is older and higher up, so Electrique is a bit more plush, within the parameters of a style that’s about as Burgundian as it gets around here.

There are a few experimental barrels in the cellar. . . .

These vines and the giant basin of virgin Jory soil below are part of Domaine Drouhin Oregon.

DDO is high up in the hills—worth a detour just for the view.

The rows are so neatly manicured it’s like they were tended by Martha Stewart.

The vines are densely planted in a more Burgundian fashion . . . but younger and hooked up to irrigation drips.

DAY THREE

Maresh Vineyard (pronounced Marsh) is further up the hill along the same road as Clos Electrique.

“Maresh isn’t a vineyard, it’s a farm,” says Kelley Fox, who works Maresh for her own label and used to make wines from here for Scott Paul. She farms biodynamically but realized early on that the vineyard didn’t really need it—the soil was already teeming with life.

This is Block One, across from the winery and a pair of 100-year-old chestnut trees. The vines were planted in 1970, which makes them some of the oldest in the Dundee Hills. The fruit here and in some other old blocks will go into the Kelley Fox Maresh Vineyard Pinot Noir. The 2012 was another highlight from the trip—solid and stony on the entry, perfumed with roses on the back end.

Patricia Green Cellars is just a quick drive away but in a completely different appellation—Ribbon Ridge. The soil is grey, marine instead of volcanic.

Kelley Fox had so many interesting things to say we talked her into coming along. Jim Anderson led us through a barrel tasting while he and Kelley dropped one knowledge bomb after another and I tried to avoid blurting out something stupid. My favorites were whole-cluster fermentations from the Durant Vineyard and the Freedom Hill Vineyard, both intensely mineral wines that turned from fruit to stone on the palate.

We were also joined by Chompers the dog.

The Estate vineyard was already planted when Patricia Green and Jim Anderson bought the property fifteen years ago. But the rows were widely spaced, so they interplanted new rows between them to increase the density.

Then Jim took us to a younger section of the vineyard they’ve been calling El Fuego. In the space of a six-foot-wide footpath separating it from the older vines below, the soil turns much blonder and the temperature contrast is like stepping into a hot car. (That’s why it’s called El Fuego.) Above, Chompers bemoans having no sweat glands and Kelley Fox attempts to take refuge in the shade.

Fin.

Potent Potables

April 5, 2015

Manfred Krankl likes to paint pretty pictures for the labels of the California Rhône blends he makes for his exclusive mailing-list winery, Sine Qua Non, which helps make them sought-after collector’s items, like when Marvel Comics used to release the same title with six variant covers and if you were a twelve-year-old with OCD you had to buy them all, plus another copy to read while the original six remained in mint condition in their limited-edition sealed mylar bags. Krankl, who is at least as talented a graphic artist as the guys who inked those covers, recently offered his mailing-list customers the opportunity to purchase a hardbound book containing the definitive archival collection of his label art, at least until the next vintage makes it obsolete and requires Krankl to offer pocket parts like the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations. For $1,500, a lucky few were even allowed to buy a limited-edition package of the book with a magnum of petite sirah, which gave the winery’s diehard fans an opportunity to do what they do best—speculate about how much more it could be flipped for in the aftermarket, the ultimate confirmation of their good taste. It is unclear whether the person who immediately listed his bottle for $15,000 on Wine-Searcher obtained his asking price. If he didn’t, someone else will.

I spoke my peace on the Sine Qua Non phenomenon in a recent issue of Noble Rot. (Get your print subscription here, or buy a digital subscription and back issues on iTunes.) My commentary on some of the wines was less than laudatory. I might have said something to the effect that they were rending the very fabric of Western Civilization. My main objection, though, was not so much to the wines themselves as to the cult of fandom that surrounds them and to the consequent uniformity of critical opinion about them. Gather a group of passionate wine drinkers around a table and it is likely to include a few people who would trade their firstborn sons for a spot on the Sine Qua Non mailing list and a few people who consider the wines a vile witches’ brew functionally indistinguishable from any number of Australian concoctions with kangaroos on the label. That same range of opinions does not exist among the population of “professionals” who rate wines for a living, whose assessment of the Sine Qua Non oeuvre recalls Dorothy Parker’s remark about the thespian who “delivered a striking performance that ran the gamut of emotions from A to B.” I did not want to have to be the one to publish the dissenting opinion, but nobody else was willing to do it. I did predict that a legion of Sine Qua Non fans would strike out at midnight, leaving their womenfolk at home to guard their places on the mailing list, and gather around my house with pitchforks. In fact, however, the mailbag turned out to brim with positive feedback and a general feeling of gratitude that someone was finally willing to say in print what so many were thinking. I was looking forward to a comfortable retirement from slaughtering sacred cows and a return to writing fun think-pieces on wines to pair with Wordsworth poems and Grateful Dead bootlegs.

But Mike Steinberger picked up on my Noble Rot article and reignited the controversy in a recent column for Wine-Searcher, “Taking Sides Over Sine Qua Non.” Like me, he was also struck by the uncanny resemblance of Krankl’s $500 blends to Aussie shiraz cartoons from the likes of Mollydooker and quipped, “I’d think twice about dumping the wines in my sink for fear of damaging the pipes.” (Gosh, I wish I’d written that.) The Steinberger take is ultimately more optimistic than mine, though. He sees the Sine Qua Non cult as a net positive for those of us who don’t drink the Kool-Aid because it gives tacky people with more money than taste a Veblen good to chase other than something like Domaine de la Romanée-Conti Richebourg, which costs more these days than a Krankl petite sirah but which Mike or I would happily drink any time the opportunity arose. My take is that the Rudy Kurniawan affair conclusively established that DRC has its own share of fanboys and BSD personalities whose appreciation for the stuff extends no further than the label, and that the gushing praise of Sine Qua Non from people who style themselves professional critics is the first step towards the inauguration of President Dwayne Elizondo Mountain Dew Herbert Camacho.

Steinberger has a theory why none of the reviewers in the spit-and-score community are willing to give Sine Qua Non anything less than rapturous reviews. “I’d say that any critic who gives whopping scores to SQN and then turns around and does the same with DRC is not really a critic,” he writes. “[H]e’s a shill or—worse—a cynic, deliberately not coming down on one side or the other for fear of offending his audience or costing himself potential readers/subscribers.” I took a similar view a few years ago on this site on the occasion of Antonio Galloni’s first California report for the Wine Advocate, in which the man who made his name championing wines like Bartolo Mascarello Barolo decided that his standards for excellence in California wine were… exactly the same as Robert Parker’s. It struck me then that this phenomenon makes perfect sense once you understand that many of the subscribers to these journals are not shopping for criticism; indeed, they’re barely even interested in recommendations anymore. None of Sine Qua Non’s votaries needs to consult the latest slate of 96+ ratings to make the decision to max out their allocation and lovingly place each bottle in the shrine-like zone of their custom-made cellar where the redwood racks are slanted to put each label on display and an unseen halogen light bathes them in a warm glow beneath a faux mural of a bucolic vineyard scene. But they’ll gladly pay anyway for a critic to issue the numerological equivalent of a sommelier’s “Excellent choice, sir.” Calling out a popular wine as the equivalent of junk food is bad for business and probably not the best way to keep the free samples flowing, either.

* * *

When I say that a wine is trash, there are really only two species of counterarguments. The first is that I’m wrong. The second is that there is no such thing as right and wrong, that one man’s trash is another man’s treasure. The relativism of the latter position is easily dispensed with, at least when it’s perpetrated by people who rate wines for a living or pay attention to those who do. Anyone who stipulates that it’s possible to place wines in a hierarchy in which one rates 90 and another rates 95 is in no position to maintain that it’s impossible to place wines in a hierarchy in which one rates 90 and another rates 50. Instead, they say that even if the critic himself deems a wine a failure, he should rate it as an outstanding wine so long as it meets other people’s criteria for excellence, which is like saying that a painting of Dogs Playing Poker is just as fine a work of art as the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel so long as it satisfies all the criteria for being a good version of Dogs Playing Poker.

For those to whom that proposition is not self-evident and need it proven empirically, permit me to recommend Charles Murray’s Human Accomplishment: The Pursuit of Excellence in the Arts and Sciences, 800 B.C. to 1950. He begins with three premises: that “people vary in their knowledge of any given field,” that “the nature of a person’s appreciation of a thing or event varies with the level of knowledge that a person brings to it,” and “the relationship of expertise to judgment forms a basis for treating excellence in the arts as a measurable trait.” In other words, art historians find the Sistine Chapel more compelling than Dogs Playing Poker because it satisfies more of their criteria for excellence in the arts, and the criteria applied by art historians are intrinsic to the very nature of excellence in the arts in a way that’s not true of the criteria applied by laymen who say, “I don’t know anything about art, but I know what I like.” In the same fashion, one can discern objective criteria for excellence in wine by mining the opinions that have been formed over generations by people who know about wine and think critically about it.

Note well that everybody believes this, even people who pretend not to. The person who insists that I am obliged to call Sine Qua Non an outstanding wine because it is an outstanding example of its style will not concede that Robert Parker is obliged to call a cool-climate pineau d’aunis an outstanding wine because it is an outstanding example of its style. Parker’s refusal to do so reflects his judgment that certain genres of wine are more profound than certain other genres, so examples of the latter can never rate as highly as examples of the former no matter how perfectly they satisfy the criteria for excellence within their own genre. And Parker is entirely correct to operate under that assumption. What he’s wrong about is the hierarchy of styles itself, not the fact that a hierarchy exists.

But wait a minute, the objection arises. Didn’t you just say that you can discern objective criteria for excellence by paying attention to what experts have to say? And isn’t Parker the Grand Pooh-bah expert here? Yes, let’s go there, because now we’re moving away from the claim that there’s no such thing as right and wrong in matters of taste, and the only question left is which one of us is wrong. Charles Murray anticipated that sort of objection, too. As he demonstrates (with highly granular data), if you consult what experts have said about art through the ages, there is broad agreement that Michelangelo is the greatest. But the last few decades have been infected by art scholars liable to dismiss Michelangelo’s esteem as Dead White European Cisgendered Male privilege and to insist that great art is about escaping the shackles of the past (shackles like, “knowing how to draw”) and creating works, like, say, an installation of the artist’s own unmade bed complete with actual urine, semen, and menstrual stains, which sold at at a Christie’s auction last year for over £2.5 million. Surely the market for this stuff must have been created by people who actually know what they’re talking about, right? Or, as Murray poses the question,

If you think that we should take the word of experts about what’s good and bad, are you prepared to accept that John Cage and Andy Warhol belong up there with Brahms and Titian? That melody and harmony are boring and outdated? That representational art is boring and outdated? That the concept of beauty is meaningless? That’s what one school of experts is saying these days.

“The direct answer to that objection,” he writes, “is that I am choosing one type of expertise and rejecting another, allying myself with the classic aesthetic tradition and rejecting the alternative tradition that sprang up in 20C.” It’s not that the postmodernists are necessarily wrong. It’s just too soon to tell. Maybe their view will become the new consensus. Or maybe it’s just a fleeting fashion. When it comes to the modern view of wine that formed only in the last two decades, I am inclined to figure the latter, because we already see signs of the fashion starting to pass, and it was never on a strong foundation in the first place—just the idiosyncratic tastes of one man with a powerful megaphone whose pronouncements on wine are starting to sound to more and more people like the musings of a contestant on the Saturday Night Live parody of Celebrity Jeopardy.

Old News

April 1, 2014

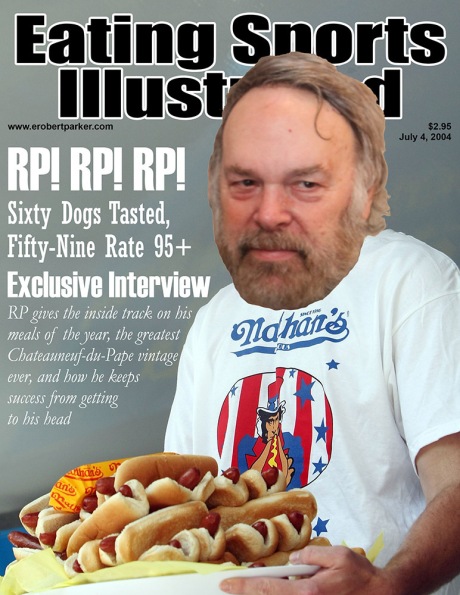

The Internet is still trying to digest the possibility that the news that Robert Parker will launch a magazine called 100 Points by Robert Parker—covering “lifestyle products, services and experiences” for “high net-worth individuals and corporate leaders”—is not an elaborate April Fool’s joke. The press release posted on his web site says:

Crafted for readers whose lives embody quality, exclusivity, originality and curiosity, ‘100 Points by Robert Parker’ understands the intelligence of a discerning audience of accomplished connoisseurs that appreciates the finer things in life, including a genuine interest in wine, and for who time to indulge their passions and pastimes is the ultimate luxury.

This glossy quarterly is not a magazine about wine. Instead, it celebrates points of view—beyond viticulture and oenology—in an elegant, contemporary environment.

Those quick to dismiss the idea have apparently forgotten that this is not the first time Mr. Parker attempted to parlay his success in wine criticism into the lifestyle-magazine market. Here are a few examples of some of his previous, sadly unsuccessful efforts:

I can’t wait for the first issue of 100 Points!

Fake Vintage Tastings

December 18, 2013

[Ed. note: The below submission was received scrawled on a napkin in a mysterious envelope bearing the markings of the United States Marshals Service. It was signed only “JK,” presumably Internet parlance for “just kidding,” but is reproduced here as readers may receive some edification from these once-in-a-lifetime tasting notes.]

There are some cellars that are world-class, and there are others that are simply magic, so when the owner of THE Magic Cellar invites you to the rec yard to crack open some rare hooch, who am I to argue?

The first piece of lumber was a jeroboam of 1975 Dom Pérignon Oenotheque Rosé. Let me be clear up front, all of these wines were jeroboams, more or less, because it turned out that three liters was the approximate capacity of the toilet tank in Rudy’s cell, where they spent their elevage. Also, it wasn’t exactly a bottle of 1975 Dom Pérignon Rosé Oenotheque, on account of that DP would qualify as prison contraband, but the best cuvée Dr. Conti could doctor up with the limited materials available at the time, which included apple juice, lemonade, cranberry sauce and chicken soup from the mess hall, a splinter of some oak-like material recovered from the vicious stabbing in Cell Block 4A, and a few other “secret ingredients” I’m not at liberty to discuss lol. Anyway, the “75 DP Rosé” was a good but not great bottle of this legendary, virtually non-existent wine, with bright acidity, a vigorous mousse as it seemed to be finishing up its fermentation in the glass, and was just marred by a few brett-like scents that might be the result of the aging vessel (93).

From there it was Burg time so we segued to a bottle (actually another jeroboam lol) of one of the wines that got us in this whole mess, a 1962 Ponsot Clos St. Denis VV. Rudy called it a “solid effort,” and he should know, and Giant Douche was all over its “earthy, barnyard” scents, which Rudy found pretty amusing because he started giggling uncontrollably. One of the newer additions to our tasting group (we call him The Warden) was less impressed, saying something along the lines of, “I don’t understand you people,” but The Chaplain obviously enjoyed it because he bogarted the bottle, so it was time to move on. A classic Ponsot CSD (94).

The 1955 Roumier Musigny had some sediment. Let’s leave it at that (DQ).

Then, Drive-By Killa, Notorious B.L.O.O.D., and Trayvon X showed up and asked what we were up to. When they found out we were in the middle of a tasting they were only too happy to join, and we were only too happy to oblige because there was plenty to go around, and besides, would you have said no? They were all over the 1919 Liger-Belair La Tache, calling it “good shit” and casting nasty glances my way whenever I went for another pour. Giant Douche found it “youthful” and “reminiscent of the ’43,” which prompted Rudy to mutter, “Um, about that ’43…” before shaking his head and trailing off. Killa, B.L.O.O.D., and X went for multiple glasses and at one point, Killa asked, “What you in for?” Rudy said, “Making fake wine,” and they all moved away from us on the bench, but then he said, “And wire fraud,” and they all moved back. We let them finish off the LT (96).

Where do you go from there? Why, Bordeaux, of course, and the jero of 1947 Cheval-Blanc was firing on all cylinders. Even The Warden seemed impressed with this one as he was left absolutely speechless and kept sniffing his glass for the rest of the flight. Giant Douche pointed out that as great as this bottle was, the ’47 is never going to be at the level of the “six star” ’24 we shared at La Paulée, to which Rudy responded, “You stupid fuck, they were the same goddamn wine the whole time.” That kind of put a damper on things so we decided it was time for a Champagne intermezzo before the next flight. Still, I’ll never turn down a glass of ’47 Cheval (98).

The 1959 Salon was everything Salon can be, and more. Giant Douche stopped stewing in his juices long enough to note its “great pitch.” Killa and B.L.O.O.D. praised its “fucked-up factor.” I remarked on its “fantastic T&A,” which made Rudy curl up into a ball and go catatonic for a little bit before finally whispering, “I don’t ever want to hear that word T&A again, ever,” and looking over his shoulder for what, I don’t know. While the wine probably would have shown better in a Zalto, the repurposed yogurt containers from the mess hall fortunately had a wide enough bowl to take in the awesome aromatics of this all-time great Salon (97).

It was getting close to lights-out and there was only one way to bring this inaugural rec yard Paulée to a perfect conclusion. What can you say about the legendary 1945 Romanée-Conti? I don’t know, but some day I’d like to find out, and until then, we had the next best thing. My head was spinning from an excess of ’59 Salon and perhaps one or more of the “secret ingredients,” but that classic RC bouquet of spices, earth, and marijuana smoke was enough to bring me back from my stupor. Rudy praised its “long, long finish,” to which The Warden responded, “Don’t worry, you’ve got time.” Giant Douche got in the last word: “the greatest wine in the world.” That says it all. Still the best wine I’ve ever had, the one, the only, ’45 Romanée-Conti, I could see that the wine was making Rudy so emotional that it literally brought tears to his eyes (99). Rudy says he still has five bottles left from his original case, which is a good thing because there will be many, many, many more nights of excess in this rec yard and there’s only one cat in this joint that can show Riker’s Island how to party, RK-style.

No Somm Left Behind

December 13, 2013

I just saw the movie Somm, and I haven’t had that much fun since 2002, when I was studying for the bar exam. The documentary follows a group of young sommeliers as they cram to take the test to be certified as Master Sommeliers. There are two things, however, that you will not see in the movie: 1) any of the protagonists actually engaged in sommeliering, and 2) the actual Master Sommelier examination itself. They must not have gotten permission to film that part, so the climax of the film consists of each protagonist walking into the exam room and closing the door behind him. The result is something that could easily have been titled Test Prep: The Movie. It would not have been a wildly different film if it focused on law students boning up on the Rule Against Perpetuities for the bar exam, or, for that matter, ambitious high-schoolers trying to ace the SAT.

The Master Sommelier examination is multipart. One part tests the candidates’ rote memorization of esoteric wine-and-spirits facts and involves a course of preparation in which each prepares for himself thousands of flash cards posing such questions as, “Name a wine producer from the Ukraine.” They all joke that the first thing they will do when they pass is burn their flashcards. Another part is a blind-tasting challenge in which candidates must taste six wines in 25 minutes, rattle off flavor-wheel descriptors for each one, and guess the appellation, grape variety, vintage, and climatic conditions, and make some general assessment of the producer. Although we don’t see the actual test, we do see several practice sessions. The candidates all have it down to a science. They call it “going through the grid,” after the Court of Master Sommeliers’ official tasting grid. Here’s how Ian Cauble does it:

“Wine 1 is a white wine, clear star bright. There’s no evidence of gas or flocculation. The wine has a light straw core, consistent to green reflections in the edge. Medium concentration of color. We’re almost coming out of like this lime candy, lime zest. Crushed apples. Underripe green mango. Underripe melon. Melon skin. Green pineapple. Palate: The wine is bone-dry. Really like this crushed slate, like crushed chalky note, like crushed hillside. There’s white florals, almost like a fresh cut flower, white flowers, white lilies, no evidence of oak. There’s kind of a freshly opened can of tennis balls and a fresh new rubber hose I get. Structure: Acid is medium-plus. Alcohol is medium. Complexity is medium plus. I’ve reached a conclusion this wine is from the New World, from a temperate climate. Possible grapes are riesling. Possible countries are Australia. Age range is one to three years. This wine can only be one thing. This wine is from Australia. This wine is from South Australia. This wine is from Clare Valley. 2009 riesling, high-quality producer.”

He’s right. But he does this a lot.

He’s sort of the ringleader of the group, the alpha, the Alex to his droogs. They all go through the grid the same way, but Cauble sells it with the most confidence. Some others of lesser constitutions get lost along the way and nearly break down in tears.

The main thing the movie captures is the constant tenseness, the suffocating terror of having to take a test which will determine the course of your life and which requires studying every waking hour because the prospect always lingers that the one extra minute you didn’t spend, the one extra flash card you didn’t review, will turn out to have made the difference between passing and failing. The movie conveys this horrible pressure vividly enough that viewers can be assured of waking the next night in a sweat from one of those dreams about having to take a final for a class you never attended, and you’re naked.

One might imagine that the fact that this test is about wine and not advanced organic chemistry or 16th century British property law would make it more entertaining. It does, but not as much as you might think. One of the striking things about the film is just how little its scenes of wine consumption actually resemble any wine-consumption setting that would be familiar to you and me. The physical elements are more-or-less the same—a group of friends gathered around a table with glasses of wine—but what’s actually going on is very, very different, almost unrecognizable as the same activity.

For one thing, none of these people are enjoying themselves. At all. They are very deliberately not making any effort to appreciate any of the wines they are tasting, only to identify them. They are also not tasting much that’s particularly interesting or that you would expect to quicken the heart of an experienced, enthusiastic wine professional—Beringer Private Reserve Chardonnay makes a cameo appearance—because they must limit themselves to the sort of commercially available archetypes likely to appear on the test. Losing oneself in a high-end grand cru matured to perfection, or a wine so spellbinding and unique that it isn’t typical of anything, would be a waste of time. And, in any event, one may only spend four minutes and ten seconds with each wine. Anything too good would just be a waste.

Cauble calls the exercise “training,” and indeed it has more in common with other forms of training than with the activity they are ostensibly training themselves to facilitate—i.e., dining. The film, ironically enough, opens by explaining that its title, “Somm,” is “Slang for sommelier, a restaurant professional who has great knowledge of pairing wine with food.” But food is a complete non-factor from the first scene to the last. None of the Master Sommeliers-in-training are consuming their wines with food. The tasting grid doesn’t even seem to address the cuisine that the wine might go with. That would interfere with the clinical environment necessary to ascertain whether a wine’s structure is “medium-plus” or just-plain “medium.”

The only people who appear to be having less fun with this than the Master Sommelier candidates themselves are their wives and girlfriends, who would seem willing to settle for four minutes and ten seconds of attention from their mates. Instead, they just get to clean up those gross spit buckets left behind in the morning. (At least there are no dishes! Just tasting-grid sheets.) The spit bucket ensures that no training sessions find themselves descending into revelry. Yes, there are wine glasses on the table, but they may as well be in a law library doing drills on the hearsay rule.

One of the other odd things the movie conveys is how the clique of Master Sommelier candidates is a subculture unto itself, with its own lore and lingua franca, as though it had evolved in complete isolation from any wider subculture of wine enthusiasts. It’s kind of like how there is one subculture of people who lift weights to compete in Mr. Universe pageants where they parade their waxed, G-stringed bodies on a stage, and a completely different subculture of people who lift weights to compete in Olympic-style events where they have to, well, lift weights. And never the twain shall meet.

Have you ever heard of Fred Dame? I hadn’t. He passed all three parts of the M.S. exam in 1984 on his first try, then helped bring the sport of Master Sommeliering to America. Among the Master Sommelier candidates he is a legend. They even have a slang term in his honor—“Daming it”—to identify a wine in 3 seconds flat on nose alone. (The typical exercise of going through the nose, palate, and structure and arriving at the right answer is referred to as “rocking the wine,” an impressive feat but an order of magnitude below “Daming it.”)

For those of us who have spent years around wine without having heard of “Daming it,” or without having had the desire to spend four minutes and ten seconds with a wine “going through the grid,” the movie does make one question what, exactly, is the point of it all. There is really only one moment in the film that addresses what any of this has to do with making someone a better sommelier, when Rajat Parr explains that when you learn to describe a wine without reference to the label, you are learning to describe it in a way that a guest can relate to. Maybe—but only to a point. That point is well short of medium-plus color concentration, freshly opened cans of tennis balls, and flocculation, whatever that is.

Since Somm doesn’t depict any sommeliers doing their actual jobs, it’s easy to lose sight of what the job actually entails. At the most basic level, they help restaurants choose wines to buy, and they help diners choose wines to drink. At the very highest level, they do all that but also have something of a sixth sense, the ability to take a wine and know not only that it belongs on their list but that it is the wine the world needs right now. To cite two of the more famous examples, the grüner veltliner trend in the last decade and the somewhat more recent revitalization of sherry both owe a lot to visionary sommeliers who found wines that nobody was interested in, evangelized for them, and made a place for them at the table and in our consciousness before anyone else even realized that there was a widespread, unsatisfied craving for exactly what those wines deliver.

All of those skills require powers of discernment. But it is not the kind of discernment deployed in four-minute tasting-grid exercises. Being able to identify a wine as a chardonnay isn’t the same thing as being able to identify it as a good chardonnay, or a great one, or as a chardonnay likely to taste good with the chef’s lobster. But however important those skills may be, they are not as testable. And thus Somm really does turn out to be a movie more about test prep than wine, perhaps even the quintessential test prep story of our age. Our heroes study and train and (most of them) ace the test, eventually. Whether the skills they have developed have done anything more for them than prepare them for the test and advance their careers is a question the movie doesn’t answer, and perhaps doesn’t even realize it’s raising.

Battle Hymn of the Tiger Bidder

October 6, 2013

Someone needs to sign Peter Tseng for a reality television show. We’re introduced to him about 35 minutes into the new documentary Red Obsession, as he lights up a pipe and walks filmmakers through his anal-retentively neat cellar and its enviable holdings of (what else?) Château Lafite-Rothschild. “I have bottles of Château Lafite everywhere,” he laughs, “in the dining room, in my office, even in my bedroom.” I must admit: Like many people who’ve been priced out of Lafite for several years now, I have cursed the Chinese billionaires who drove its prices to unprecedented heights for no apparent reason other than a vague perception of Lafite as “the best of the best.” But Mr. Tseng is such a wonderful caricature that it’s hard to hold a grudge. With his Sherlock Holmes pipe, Bond-villain cat, and sideburned, mustachioed visage, his screen personality seems a roughly equal admixture of Hugh Hefner and a boss in a kung-fu movie. The Hefneresque aura is enhanced by the fact that he made his fortune in what the narration calls “the pleasure business,” and his infectious laughter suggests that the absurdity of becoming one of the richest men in the world from a dildo empire is not lost on him. “When I was younger, I preferred sex,” he chuckles, “but as I get older, I prefer wine.”

Red Obsession is a story in three parts. The Chinese billionaires don’t come in until the second act. The film opens with a time-lapse shot of Médoc vineyard plains as a cloud cover rolls in. From there, it interpolates some of the most breathtaking vineyard cinematography ever filmed with interviews from Bordeaux VIPs such as Petrus’s Christian Moueix, Palmer’s Thomas Duroux, and Paul Pontallier (et fils) from Château Margaux, each of whom attempts to articulate just what it is that has made Bordeaux the gold standard in wine over the last several centuries. That’s familiar marketing spin, of course, but some of them, particularly Moueix, come across genuinely passionate. It’s a passion that seems easy to share as one absorbs the imagery: Bordeaux has never looked this beautiful, even in person. Shots of Château Lafite from the same vantage point as its iconic label seem quite literally to bring the scene to life; the effect seems like what I imagine it must have felt like for a generation of silver-screen moviegoers to see black-and-white turn to technicolor for the first time in the Wizard of Oz. With its time-lapse sequences, aerial panoramas, and radiant landscapes, it struck me that the vineyard cinematography itself was enough to carry the film. Cut out the interviews, add a Philip Glass soundtrack, and it could pass for an installment of Godfrey Reggio’s ’Qatsi trilogy.

I actually wonder if an homage might have been specifically intended, because it isn’t just the imagery that reminds me of Koyaanisqatsi‘s “life out of balance,” but a good part of the narrative arc, too. In Koyaanisqatsi, serene desert landscapes ultimately segue into scenes of monolithic skyscrapers and soul-crushing urbanity, most powerfully in a sequence where Glass’s “The Grid”—essentially twenty minutes of building adrenaline—plays over time-lapse reels of thousands of office workers endlessly churning through congested streets and subway turnstiles in filthy pre-Giuliani Manhattan. In Red Obsession, the second act begins with a transition from pastoral Bordeaux to modern Beijing, dramatized by a time-lapse shot of a thirty-story skyscraper being erected in a mere 15 days.

The ChiComs had to be dragged kicking and screaming into modern civilization but having gotten there they are apparently determined not to be outdone by anybody. They are now enjoying a bender of economic growth that has produced literally too many billionaires to count. The inevitable result is a lot of conspicuous consumption and kitsch, which Red Obsession portrays honestly, but also somewhat sympathetically, nodding to the historical context. “If they have lived through the horrors of the Cultural Revolution,” remarks wine writer Ch’ng Poh Tiong, “this means they’ve gone to hell and come back.” So they have earned the right to enjoy their billions.

Nevertheless, the film does leave a certain irony about this chain of events unacknowledged and unexplored. The Cultural Revolution went even further than the rest of history’s many spectacularly failed experiments in communism and became a mass pogrom against every aspect of China’s culture that was not explicitly Maoist, including both its own traditions as well as any semblance of Western influence. Suffice to say that possessing a bottle of Lafite would certainly have qualified as “counter-revolutionary.” Yet the same Party with the purges of the Cultural Revolution on its résumé is presiding over the minting of nouveau riche capitalists fixated on Lafite and Prada and Gucci and, for that matter, any other brand in the world with the trappings of Western European luxury. “Wine now is a new Silk Road,” remarks one Chinese wine merchant in the film. “It is one of the intermediaries to connect China to the rest of the world. You look at China now, they’re all dressed in a shirt and tie like me. It’s part of Westernization they wear on the top of their skin. Now you talk about wine . . . they swallow Western civilization, inside the body.” Once it was a nationalist act to smash these idols; now it is a nationalist act to drink them in. Robert Frost was right: “The trouble with a total revolution / . . . / Is that it brings the same class up on top.”

Red Obsession also omits any mention of the role that China’s ruling Party itself has played in the Lafite fetish and the luxury-goods market in general. The only people interviewed in the movie are presumably buying wine for their own consumption. Nobody was going to be caught on camera admitting he needs to maintain a gift stash of thousand-dollar bottles of wine for purposes of bribing Party apparatchiks with not-inconsiderable influence over who can do business in their zone of influence. But two years ago, an executive of a government-owned oil company in China was caught up in a mini-scandal after it was discovered that he had spent hundreds of thousands of dollars of company money buying up the 100-point-Parker-rated ’96 Lafite—“allegedly to sweeten deals with local officials,” reported Decanter.

In any event, while Red Obsession tells a less than complete story of the Bordeaux mania in its heyday, it deserves a lot of credit for recognizing that the story is worth telling at all. There is more truth in this movie about the way wealth is earned and spent in the modern world than there is in the entire Thomas L. Friedman œuvre. I am particularly fond of the movie’s juxtaposition of Lafite’s Charles Chevalier offering his explanation of how Lafite achieved its esteem in China—“the secret of Lafite is in the soil itself . . . there is something by the nose which is [ . . . dramatic hand-wave . . . ] Lafite style”—with the explanation offered by Julien Pouplet, a French ex-pat on the ground in China as a wine consultant: “Yesterday a customer of mine told me, we think in China it is very good for the health of a lady for the skin. If you drink Lafite you have beautiful skin.” He rolls his eyes.

The final part of the movie runs through some of the consequences of all this—and hints at the endgame. There is some coverage, of course, of the problem of counterfeits. We also see some of the Bordelais and old-timers in the trade acknowledging that they have abandoned their historic customers—some even lamenting that fact, or at least pretending to lament it while barely managing to suppress the urge to make cha-ching sound effects, strip naked, and perform an Uncle Scrooge dive into a vat of euros. But the real plot twist comes when Sun Hongbo walks us through the grounds of a stately, turreted Old World chateau surrounded by a Medieval town and vines in the familiar Bordeaux fashion—except that the estate is not in Bordeaux. It’s Chateau Changyu AFIP, “80 kms north of Beijing.” Mr. Sun explains that he traveled through Europe for ten years, “visited many chateaux and famous villages,” and made up his mind “to build a European town and chateau in China.” But the unspoken message seems to be, What, you thought we were going to keep sending you our money and buying all your wine forever? Two can play at this game, you know. “It now seems that Bordeaux’s largest customer is becoming its competitor,” intones narrator Russell Crowe. “China is now planting over 20,000 acres of new vineyards every year.”

That might be bad news for the Bordelais, but it actually offers consolation that for at least some participants in China’s latest obsession, there is a genuine passion for wine as wine and not simply as a luxury good that serves the same function as a Prada bag. The only reason to plant vines and attempt to make fine wine in a place that has no historic culture of winegrowing or wine-drinking is if you want to help create one. That this is even thinkable in China is, in some sense, an even more remarkable cultural transformation than its embrace of market capitalism.

The Chinese never had a wine-god but the Greeks called theirs Dionysus. In his 1965 book of that name, subtitled A Social History of the Wine Vine, Edward Hyams wrote:

Now it is self-evident that there are very large tracts of the world between 30 degrees and 51 degrees North and between 30 degrees and 51 degrees South where there are no vineyards. There are indeed, particularly in Asia, many thousands of square miles of perfect vineyard land in perfect vineyard climates, where grapes are hardly grown at all, and then only for dessert fruit or dried fruit. It seems that the wine-vine is excluded from some parts of the world which would be congenial to it by influences other than climatic or geographical. These influences are subtler: they are social, almost religious. There are those who are people of the vine; and others, simply, are not; and the curious facts touching the repeated introduction of the vine into China, described in Chapter VIII, bear out this contention. The wine-vine is very much a plant of Mediterranean man: it is an art of the Mediterranean cultures; it is deeply involved in their religions, both ancient and modern; for even the positive, the conscious rejection of wine by ancient peoples of the vine under the influence of Islam is a negative involvement very different from the total indifference of the Chinese or the merely commercial influence of the Japanese. There are, in short, peoples whose cultures have never included the vine and which have rejected it when offered; and this is the other limit set to the expansion of the vineyards.

European man overran the whole planet; he has now withdrawn or is withdrawing from parts of it, leaving them again to the older cultures which already possessed them and were fossilized, or to any new ones which may arise. Curiously, the places he has withdrawn from are those where the vine, too, was hopelessly alien; and the places he has made permanently his own are places where the vineyards have flourished. One might almost regard Vitis vinifera as his peculiar hallmark; and in his new absence one would expect to find it lingering only among those people who have taken something fundamental from Mediterranean culture, the Christian religion for example. For, Lord Snow notwithstanding, the Western type of tool-making, called ‘Science’ and now œcumenical, while a part of a culture in the archaeological sense of the word, is not fundamental to culture in our sense here: a Chinese may accept our nuclear physics; he rejects our poetry, our music and our wine-vine. There is a sentimental illusion, fostered by liberals, that though the minds of men may differ, the heart is the same everywhere; the curious history of the association between men and grape-vines is part of the evidence that the converse may be true.

For a Beijing billionaire, a hoard of Lafite must make for a pretty nice trophy of China’s economic triumph over the debt-ridden, declining West, but the whole obsession—and the growing vineyard footprint—does raise the intriguing question of just who is conquering whom.

Detour

August 9, 2013

We interrupt your irregularly scheduled programming for a brief detour. The site may have been quiet, but I haven’t been—you’ll just have to read my three most recent articles somewhere else.

First, you surely know Lars Carlberg’s name as one of the founders of the late, great Mosel Wine Merchant, which brought such producers as Peter Lauer, Immich-Batterieberg, and Steinmetz to the US and changed the way many people, myself included, drink riesling. The first time I tasted one—Peter Lauer’s Senior—my immediate reaction was, “Where have you been all my life? And why doesn’t everyone make riesling like this?” Lars now writes a Mosel wine guide at larscarlberg.com focused on in-depth producer profiles and recent tasting reports, and he asked me to contribute a guest article. Opening lede:

André Simon wrote in Vintagewise—his 1945 “Postscript to Saintsbury’s Notes on a Cellar Book“—that the wines of the Mosel saw “a very marked and most regrettable difference not only in the individual quality but in the general style of the wines made after 1915 and those made before 1914.” That is an intriguingly specific place to draw a line. Style is more often a fluid thing, evolving slowly based on changing tastes and the whims of fashion. But a few very specific things happened in 1914.

There was, of course, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and the outbreak of World War I, but (as Leslie Nielson might have said in the movie Airplane!), that’s not important right now. . . .

Read the rest at larscarlberg.com.

Next, I am very proud to say that I’ve now had several articles and book reviews printed in my favorite wine magazine, the World of Fine Wine. The latest issue features my review of three new books on Bordeaux—Neal Martin’s Pomerol, Stephen Brook’s The Complete Bordeaux, and Jane Anson’s Bordeaux Legends. You can also find my report on Abe Scholium’s Metaphysical Lecture Series, and find out what his Scholium Project Gardens of Babylon petite sirah has in common with a foggy landscape painting hanging in Washington, D.C.’s National Gallery. So visit your local newsstand today—or read the issue on the brand-new World of Fine Wine iPad app.

I Love the Smell of Commerce in the Morning

June 30, 2013

It’s officially summertime, so everyone is drinking some rosé. A lot of it will be from Domaine Tempier (it’s some kind of unwritten law). But the Peynaud family behind Domaine Tempier once almost gave up making it. As related by their importer Kermit Lynch in his seminal Adventures on the Wine Route, “I had to argue the case for the rosé of Domaine Tempier . . . with its own winemaker!” Bandol had the terroir for great reds, Jean-Marie Peynaud maintained, so the rosés should be left to the lesser coastal appellations. Lynch protested: “There is a place for a pretty wine like that, and, moreover, the rosé has something to do with the personality of the Domaine Tempier, the joie de vivre. When one arrives, one is greeted with a cool glass of rosé. That’s valuable.” Peynaud conceded the point, and said, “in fact it is in that spirit that I make it.”

Tempier never took out a glossy magazine ad depicting the scene, but had it done so, it would have been engaging in what the Madison Avenue types call “lifestyle marketing.” They’re not so much selling a pink wine as the joie de vivre, the spirit of Provence. You are probably not drinking your Tempier on a sun-drenched Provençal veranda while a Mediterranean breeze wafts the scents of the garrigue over your salt-flecked hair—you may, in fact, be sneaking sips while trying to tap out an email on your Blackberry and hoping Thomas the Tank Engine occupies your toddler long enough to let you finish your dinner—but the wine reminds you of some of the little things you can do to nudge yourself to a more civilized existence. Maybe when guests arrive, you end up greeting them with, “Hi! Have a seat, grab a glass of wine!” rather than, “Hi! How was the traffic? What route did you take?” And when there is wine on the table, you’re forced to slow down a little bit. Meals aren’t just about pausing to refuel before moving on to the next obligation. An evening with wine is different from an evening without it. By extension, life with wine is very different from life without it.

The same is not true about Coca Cola or beer. So it strikes me that people who are in the business of selling wine have a pretty good story to tell. They have a beverage that doesn’t merely satiate thirst or taste good, but promotes a civilized way of life in every culture where it is a fixture.

I was recently surprised, however, to see some disagreement about this among some people who are as appreciative of wine in all of its facets as anyone. It started when Eric Asimov responded to a post on Twitter by an Oregon winery lamenting that “[t]he industry has largely failed to communicate to consumers that wine is food.” Asimov quipped, “It hasn’t tried. Prefers ‘lifestyle.'” He added: “Promoting as aspirational commodifies as luxury good, intensifies anxiety.” Asimov’s argument is that we should want wine to be treated as a staple of the table, something as normal to see there as salt-and-pepper shakers. Bruce Schoenfeld then joined the discussion to make a similar point: “Lifestyle marketing is about making wine appear to be a piece of a desirable way of living. . . . Except promoting wine as a lifestyle adjunct comes at the expense of promoting it as a staple food.”

But I don’t see any tension between those two things myself. Promoting wine as a staple food is to promote it as a piece of a desirable way of living. To say that wine should be a staple of the table is essentially to say that we should promote the kind of culture and lifestyle where it is treated as such. Lifestyle marketing needn’t mean luxury marketing.

Asimov has a point, though, that the kind of lifestyle marketing that makes sense to me may be more theory than reality. If we see it at all, it is in missives from specialty retailers, not from wineries that actually do produce enough of the stuff that being perched on every dinner table is a realistic business objective. I was thus inspired to spend an afternoon browsing some of the glossy wine and food magazines I have lying around to see exactly how those brands promote themselves and what lifestyle message they are trying to convey.

Most of them, to be sure, don’t have much of one. More than half the ads consisted of a close-up shot of a bottle occupying most of the page pasted on top of a pretty vineyard scene with a generic slogan like “The Quality is in the Bottle.” (The guys at the ad agency probably go with this one when it’s 4:59 on a Friday and they have nothing else—“Oh, what the hell! Let’s just give ’em the old bottle-and-vineyard pic special and call it a day.”) Some others were slightly more imaginative, though. Here are the results.

Product: Penfolds Grange

Copy: The headline “100/100,” with a blurb promising that “it will only get finer with time” and explaining that “[t]he 2008 Grange has been awarded a perfect score by Robert Parker’s Wine Advocate, a respected publication.”

Graphics: A two-page spread of a faux-candlelit dungeonesque wine cellar, of the sort a vampire might have built in his castle if he had exceptionally tacky taste in both wine and wine-cellar architecture. A bottle of Penfolds Grange and four empty glasses sit on a table in the foreground. (There is no food, but that is probably okay if you vant to drink some blood.) In the background, behind a bricked archway, is the cavernous cellar space featuring what appears to be some kind of objet d’art on the wall (abstract and geometric except for its incorporation of vine-twigs) and enough racking to hold several dozen bottles of wine. The photograph is captioned, “Private cellar, New York, USA.”

Message: If you’re the kind of person who doesn’t find this wine cellar tacky, why don’t you try our top-of-the-line shiraz? You probably won’t find that tacky, either.

Product: San Pedro GatoNegro

Copy: “Why are 3 bottles of GatoNegro opened every 2 seconds somewhere in the world? GREAT WINE + EXCELLENT PRICE.” [ed. note: Can this really be true? By my calculations, which started with getting a song from Rent stuck in my head and multiplying 525,600 minutes by 60 by 1.5 bottles per second, that’s over 47 million bottles.]

Graphics: A bottle of San Pedro GatoNegro Cabernet Sauvignon from the Central Valley of Chile looming large in the foreground a la the 4:59 special, but pasted on a background photo of a rooftop party at dusk populated by just the sort of clean-cut—but not too preppy—attractive, diverse 20- or 30-somethings who have just graduated to the kind of parties where you don’t have to yell over the music and beverages are served in actual glasses.

Message: Maybe you’re not the kind of person who wants to drink the same thing that other people are opening every two thirds of a second. Maybe you’re the kind of person who stays home alone reading the Internet every Saturday night because he has no friends. Wouldn’t you rather buy a bottle of GatoNegro Cabernet Sauvignon and get invited to rooftop parties where young, attractive people mingle and have a much more fulfilling, mature time than all those ruffians down below drinking beer and watching sports? And did we mention it’s cheap?

Product: Marchesi Antinori

Copy: “Behind every Antinori label is a 600-year pursuit of excellence.”

Graphics: A bottle of Villa Antinori IGT Toscana occupying the full height of the page, next to a montage of vintage paintings and photographs of Antinori family patriarchs (including Renaissance-style oil portraiture, a sepia-toned photograph of a gentleman with a handlebar mustache, etc.) along with vineyard and winery imagery (barrel room, Tuscan hilltop vista).

Message: Buy our $10 sangiovese and you, too, can be an Old World aristocrat. Oh, wait, no you can’t. Why don’t you buy our $10 sangiovese anyway and give our noble bloodline the respect we deserve, you filthy plebeian?

Product: Rodney Strong Cabernet Sauvignon

Copy: “Place Matters. Sonoma County”

Graphics: A typical example of the bottle-and-vineyard pic genre: a point-blank shot of Rodney Strong cabernet occupying most of the page, perched on rustic wood slats (one imagines it might be a picnic table) pasted on top of a monochrome scene of an expansive wine-country vista, vines in the foreground, a lush, forested hillside in the background. A gratuitous color illustration of a grapevine twig with a few leaves is wrapped around the bottle like a laurel.

Message: Gosh, that vineyard is pretty. Surely the wine inside must be too!

Product: Liberty School Paso Robles Cabernet Sauvignon

Copy: “American Classics Are Never Left Behind.” In the corner, a notation that the wine rated 90 points and a #3 Best Buy from Wine Enthusiast’s Top 100 Best Buys 2012.

Graphics: A whimsical photograph of an attractive young couple boarding a private Gulfstream jet and reaching down from the staircase to grab a bottle of Liberty School Paso Robles Cabernet Sauvignon from a silver tray held aloft by a white-gloved stewardess in a naughty vintage Pan Am–style uniform just barely managing to contain her ample bosom, standing alongside a red carpet while a grounds crewman loads six cases of Liberty School Paso Robles Cabernet Sauvignon (prominently branded “Made in America”) into the back of the plane and the pilot stands by, impatiently staring at his wristwatch.

Message: The imagery is so exaggeratedly tongue-in-cheek that the private-jet lifestyle is more of an ironic joke than an aspirational lifestyle promise. Thus, the aspirational lifestyle promise is that this is a wine for people who don’t take themselves too seriously, and get ironic jokes. My favorite of these ads!

Product: Butternut, The Rule, Volunteer, and Bandwagon brands from BNA Wine Group

Copy: “Special Occasion Taste You Can Enjoy Every Day,” followed by a signed quotation from winemaker Tony Leonardi: “Napa Valley’s in my blood, and I blend that heritage with expertise from our Nashville headquarters to create wines rich in taste and value.” A QR code promises “a chance to win a FREE trip to Nashville,” including “airfare, hotel, entertainment, a private tasting, wine and a VISA gift card.”

Graphics: Full-page bottle shots of Butternut California Chardonnay and The Rule Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignon, pasted on a photograph (with a filter applied to give it that washed-out, 1970s family-album look) of Tony Leonardini in blue jeans and plaid shirt walking a dirt road surrounded, it appears, not by a carefully manicured vineyard, but by wild brush.

Message: We ain’t fancy-pants wine conn-oy-sooers over here. Look at me, I’m from Nashville, I wear plaid, and I probably even drive a beat-up truck, but I can still drink cabernet instead of Coors and not feel like any less of a man.

Product: “Austrian Wine”

Copy: “Taste culture. Come and visit some of the world’s most picturesque wine landscapes along the Austrian Danube. Taste crisp, delicious wines with regional food specialties in fine restaurants and cozy wine taverns.”

Graphics: A glass of a crisp, delicious white wine in the foreground against a background of a picturesque wine landscape along the Austrian Danube, with a town nestled among the vines which probably contains some fine restaurants and cozy wine taverns.

Message: No subliminal messaging here! Did we mention the crisp, delicious wines, the fine restaurants and cozy wine taverns, and the picturesque landscapes?

Product: Bonterra

Copy: The headline, “Bonterra / Pure Harmony” with a paragraph explaining: “At Bonterra, we grow wine organically and sustainably, treating the land with deep respect. We build birdhouses in our vineyards for the bluebirds and finches, who thank us by snapping up insects that would otherwise harm our crops. They get a tasty dinner, and you get pure, flavorful wine made from our organically gown grapes. That’s what we call being in tune with nature.”

Graphics: A bottle of Bonterra something-or-other (variety and region cropped out of the picture, but it’s red) with a bird perched on top, against a plain gray background.

Message: You already drive a Prius, spend twenty minutes a day sorting your recyclables, and Facebook-defriended everyone you know who isn’t convinced of global warming, including your mom. You’d probably be really into the natural-wine scene if you’d ever heard of it, but you’re reading a glossy national magazine so we bet you haven’t. Have some Bonterra instead.

Product: Fontanafredda Barolo

Copy: The headline, “Fontanafredda / Let Your Barolo Journey Begin,” with a short historical precis informing us that “Barolo is often referred to as the King of Wines, and Fontanafredda is among the most noble of them all. Established in 1878 by the first King of Italy, Fontanafredda now blends time-honored winemaking techniques of the past with today’s most advanced technology. Perhaps that’s why every wine we produce becomes a modern classic. Start your Barolo journey with a truly regal wine—Fontanafredda—and you’ll never look back.”

Graphics: Yet another full-page, close-up shot of the bottle—a 2007 Serralunga d’Alba Barolo—whose label’s alternating dark and light gray stripes appear inspired by a prison uniform. There is no imagery in the background besides a continuation of the stripe pattern from the label.

Message: You can drink like the King of Italy and dress like an escaped convict.

Product: Chateaux Canon-la-Gaffeliere, Gazin, Smith Haut Lafitte, and Branaire-Ducru

Copy: “Les 5 / born under a lucky star”

Graphics: Proprietors S. von Niepperg, N. de Baillencourt, F. & D. Cathiard, and P. Maroteaux standing beside or leaning against their respective wines as though the bottles were ten feet tall, all dressed in dark, bespoke suits accessorized with the requisite master-of-the-universe cuff links and pocket squares.

Message: There is a wine for every occasion. These are the wines for occasions when you’re wearing a pocket square.

Product: Zonin Prosecco

Copy: “Enjoy the simple moments of life. [signed] Francesco Zonin.”

Graphics: A bottle of Prosecco and a gentleman with long, flowing dark hair, in a black suit jacket and a white dress shirt, top two buttons undone—presumably Francesco Zonin, but a dead ringer for a soap-opera star, a romance-novel cover model, or the sort of man who likes approaching discontented married women with a line like, “Your eyes have a—how you say—sparkle. Come back to my villa and I will make love to you for hours”—holding aloft a glass of bubbly Prosecco.

Message: Cougars, start your engines.

Product: Brunello di Montalcino

Copy: “Brunello di Montalcino”

Graphics: A silhouette of a bottle on a black background, no label or other identifying marks visible. In the corner, the logo of the Consorzio del Vino Brunello di Montalcino.

Message: Did you know there’s such a thing as Brunello di Montalcino? It comes in bottles!

Product: Cantina di Soave Re Midas Soave and Corvina Rosso

Copy: “You Won’t Go Wrong with the Right Italian.” In smaller text, a paragraph telling us the Soave is “elegant, bursting with crisp citrus, melon and pear,” adding as a postscript, “Also, you’ll love Re Midas Corvina for its red berry, currant and cherry flavors!” and in between extolling their “accolades from the top wine publications” and ability to “partner[] flawlessly with an exceptional range of cuisines.” Concluding text: “So, if you enjoy Pinot Grigio, delight in Re Midas Soave—the right Italian.” On the bottom, movie-poster style quotes of “Extreme Value”—Wine & Spirits, “Best Value”—Wine Spectator, “Best Buy”—Wine Enthusiast, etc.

Graphics: A bottle each of the red and white with a left-hand column depicting dishes from the aforementioned “exceptional range of cuisines”—a lobster, Greek salad, tortellini, peppers, grilled chicken, salmon and tuna sushi, spaghetti with fresh tomatoes, and wedges of cheese.

Message: You want a staple of the table? We got your staple of the table right here. If you enjoy pinot grigio.

It Was a Dark and Stormy Wine

April 6, 2013

“It was a dark and stormy night,” wrote Edward Bulwer-Lytton in the first sentence of a novel whose name nobody bothers to remember; “the rain fell in torrents, except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the housetops, and fiercely agitating the scantly flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness”—thus reverberating through the ages and inspiring the world’s preeminent annual awards ceremony for bad writing. The Bulwer-Lytton Fiction contest, now in its 31st year, challenges writers to compose “the opening sentence to the worst of all possible novels.” I think the 1997 grand-prize winner was among the best at capturing the spirit of the contest:

“The moment he laid eyes on the lifeless body of the nude socialite sprawled across the bathroom floor, Detective Leary knew she had committed suicide by grasping the cap on the tamper-proof bottle, pushing down and twisting while she kept her thumb firmly pressed against the spot the arrow pointed to, until she hit the exact spot where the tab clicks into place, allowing her to remove the cap and swallow the entire contents of the bottle, thus ending her life.”

But I’m not sure that Bulwer-Lytton or any of the illustrious winners of the contest bearing his name ever strung together anything quite as self-indulgently prolix, pretentious, and riddled with clichés as the typical wine tasting note. Here are just some of the stock phrases and fifty-cent words that aspiring and imbibing Bulwer-Lyttonites pack into their tasting notes as compulsively as someone refreshing his email or Facebook feed while sitting and waiting for his number to be called at the DMV—but which, if you really think about it, either don’t say anything, or say a whole lot that isn’t true.

All that hedonism. — There is probably no single word more misused in the lexicon of tasting notes than “hedonistic.” As of this writing it appears in no fewer than one billion Wine Advocate tasting notes and is essentially Robert Parker’s shorthand for everything he loves to see in wine—unctuous concentration, syrupy fruit, and minute-long finishes. Whatever the merits of these attributes, they are not, I am almost embarrassed to have to point out, what anyone customarily associates with a life of hedonism. It is quite impossible to imagine the Emperor Caligula admiring the viscous legs of an oily-black grenache in his Riedel glass in one hand and an hourglass in the other to time the finish while bored concubines file their nails in the background wondering what they bothered getting naked for. No, the wine you would want to pair with a Roman orgy is one you can guzzle with such abandon that 750 milliliters is a woefully insufficient single serving. It should be juicy and full of energy and capable of delivering a visceral joy, not an analytical project—I think of something like a Clos Roche Blanche gamay, Peter Lauer’s “Senior” riesling, or even a fun, tingly little dolcetto. Frankly, if you’re writing a tasting note at all, which is basically a flowery lab report, the wine probably wasn’t all that hedonistic. If, on the other hand, you put down your pen and had to resist the urge to execute a Gatorade dunk, then you’re getting much closer to hedonistic territory.

The fruit salad. — Let’s be clear about this. Cabernet sauvignon does not taste like currants. Pinot noir does not taste like cherries. Riesling does not taste like apples. They taste like what they are. Cabernet tastes like cabernet, pinot tastes like pinot, riesling tastes like riesling. The analogies to other fruits are, perhaps, of some arguable potential use to someone who’s never tasted a grape before, the same way describing a zebra as a horse with stripes is helpful to someone who’s never seen a zebra but extremely unhelpful if you are aspiring to describe what is notable about one particular zebra. But that’s where the usefulness ends, and I’m not sure it even goes that far. Nobody has ever bit into a cherry and remarked that it tasted like a Gevrey-Chambertin, a fact which ought to prove conclusively that any Gevrey-Chambertin’s resemblance to a cherry is so distant it’s barely worth noting. One hundred pinot noirs in a horizontal tasting will all resemble each other more than any one of them will resemble cherries (even if you include some Griottes!). If you had to comment on just one of them, saying “textbook pinot noir” would, more often than not, exhaust almost everything that needs to be said about its fruit. But this is not a viable option for someone who is paid to taste a hundred wines in one sitting and comment individually on each one of them. The critic cannot spend very many column inches talking about what they have in common. Nobody would have the patience to persist through so much redundancy. The alternative is to dwell on the differences, even if those differences don’t have very much to do with what makes each wine what it is. Thus comes the cavalcade not just of cherries but of maraschino cherries and kumquats and pomegranates and hermaphroditic Himalayan elderberries. Obviously, each of these lists is a completely irreproducible result. I do not believe for a moment that there is a human being alive who is capable of tasting the same wine and composing the same fruit salad twice even within ten minutes of each other, to say nothing of what happens when two different people attempt the exercise.

“Literally.” — Poor Antonio Galloni has tasted wines which “literally hover[] on the palate” (2010 Jadot Clos St. Denis), “literally float[] on the palate” (2009 Comtes Lafon Volnay Santenots-du-Milieu), “literally wrap[] around the palate” (2008 Montepeloso Nardo), “literally explode[] on the palate” (2009 Grivot Clos Vougeot, 2006 Cerbaiona Brunello di Montalcino, 2006 Voerzio Barolo Sarmassa), “literally burst[] from the glass,” (2009 Shafer One Point Five Cabernet Sauvignon, 2004 Geoffrey Brut Millesime), “literally fill the room with intense perfume” (2005 Aldo Conterno Barolo), and “literally send shivers down my spine” (2006 Ornellaia). But does the 2009 Jadot Puligny-Montrachet Folatieres, which “literally fills out in every dimension,” fill out the fourth dimension as much as the 2006 Gaja Sperss, whose finish “literally lasts an eternity”?

“Painfully intense.” — This is apparently supposed to be a good thing (at least when it’s not literal!). Intensity is good, so “painfully intense” must be better, and “excrutiatingly intense” better still. Wines used to perform actual waterboarding are automatic 100-pointers.

The “deft” use of oak. — Putting wine in an oak barrel is not origami, or a close-up magic trick, or a maneuver on the uneven parallel bars. Doing it deftly just means one didn’t spill. In tasting notes, deft oaking tends to mean that the wine doesn’t taste oaky, or that it does taste oaky but not too oaky, or that it tastes very, very oaky, but expensive oak.

Gratuitous French. — “Pain grillé” means “toast,” “cassis” means cherries or currants, and “en magnum” means that someone, for some reason, not only felt it vitally important to let the world know he has a big, swinging bottle, but that everyone else’s big bottle is a country hick in comparison. My magnum did a semester at the Sorbonne, and can order in French. (As long as it doesn’t have to speak any more French than a two-letter preposition.)

Timed finishes. — As much fun as it is to imagine fat wine critics wearing stopwatches around their necks in gym-teacher lanyards to time all those 55-, 65-, or 75-second finishes with the requisite precision, science says that those finishes have pretty much nothing to do with the wine and everything to do with how much bacteria is living in one’s mouth. In any event, those with a fetish for long aftertastes can forego the wine and eat some garlic. The finish will go on for hours!

Kudos. — It’s the emptiest of empty surplusage, tacked to the end of the note when a critic fears that even the purplest prose is insufficient to convey the magnificence of the wine in front of him. “Kudos to proprietor Frenchie McFrenchman for fashioning such an extraordinary effort!” It took me awhile to realize why I find it so grating (other than sheer overuse), but I finally put my finger on it. It is a nice thing to happen upon a wine that one enjoys. It is quite another thing to presume that one’s own personal enjoyment is such a universal moral imperative that catering to it represents some kind of heroic struggle against adversity for which honorifics are due. Ezekiel 25:17. The path of the righteous winemaking consultant is beset on all sides by the inequities of precious sommeliers and the tyranny of the anti-flavor elite. Kudos to he who, in the name of high scores and price hikes, shepherds the grapes through the valley of reverse-osmosis machines and 100% new oak, for he is truly his brother’s keeper and the finder of lost children. . . .

I am sure I have overlooked many other worthy clichés. Readers are hereby invited to comment with their own nominations, preferably in the form of fictional tasting notes for the worst of all possible wines. There will be a prize for the winner!

References and further reading: Bulwer-Lytton’s Paul Clifford . . . Winners of the Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest . . . The Oregonian on “Retro-nasal wine appreciation” . . . Andrew Jefford on tasting notes at Decanter.

Going Back to Bordeaux

March 2, 2013

Unlike the protagonist of Bob Dylan’s “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues”—who “started out on Burgundy but soon hit the harder stuff”—the usual path these days seems to be for people to start out drinking wine from California. Some stick with it, while others tire of the usual formula of jam + wood and sooner or later find themselves migrating to the Old World. My own biography, however, is none of the above. I got my start on Bordeaux.

I was in a summer program in France before my junior year of college, attempting to learn the French or at least get a credit that would finish out the foreign-language requirement. I failed miserably at the former while succeeding in somewhat dubious fashion at the latter (learning an interesting lesson in American-style grade inflation along the way, when my 13/20 mark for the semester—“Assez bien,” literally: “Good enough”!—translated into an A- on my college transcript). The school was in Annecy, an idyllic postcard-snapshot of a town in the Savoie. The area was and is much more famous for its cheese than its wine, but I enjoyed many afternoons of cheap, gulpable local whites out of pichets or in kirs, and plenty more over dinner. The family I was lucky enough to be boarded with seemed to host students more out of a desire to have mouths to cook for than any financial necessity, and there was a bottomless supply of cheap mondeuse on the table. (We speculated jokingly that it was the same bottle refilled every day from a gas-station-style pump in the yard.) I quickly got curious enough to start exploring the wares at the wine shops in town and asked my host one day what the best wines in France were. “Bordeaux,” he responded, and then said again a few more times, “Bordeaux,” refusing all entreaties to elaborate and using the tone of voice I imagine Ring Lardner captured in his classic line, “Shut up, he explained.”

I had only two criteria to guide my Bordeaux purchasing. The first was the label. Any bottle with an etching of a stately château and a fancy cursive script got preference. The second was age. The shelves were mostly stocked with newly released 1994s, but there were some older bottles here and there. I had somehow picked up on the fact that 1989 was supposed to be a pretty special vintage and bought those when I saw them.

Obviously, I had no clue what I was doing. I didn’t know whether Haut-Médoc was a place or a grape. I had certainly never read a wine magazine and had no idea I was supposed to be judging what I was drinking based on whether it approximated red currants, lead pencils, or anything else. Nor had I ever heard used, or ever thought to use, the word “complexity” to describe the desirable attributes of a wine. Rather, if you had asked me to identify what distinguished the ones I liked from the ones I didn’t like so much, I would have used the word “smooth,” a term which is today practically a shibboleth of complete ignorance about the standard vocabulary. But “smooth” was the key for me. Some wines felt coarse and dry going down the gullet, like the cheap table mondeuse. But others went down as easy as water, the gastronomic equivalent of slipping into your most comfortable pair of shoes. A 1989 cru bourgeois guzzled on a picnic blanket with a girl from California while watching Bastille Day fireworks fit into that category and remains my Platonic ideal of what “claret” should be for reasons—believe it or not—having nothing to do with the girl. One of the reasons it would never have occurred to me to describe it as tasting like red currants or any other kind of fruit is that it didn’t taste like fruit at all. It tasted like wine.